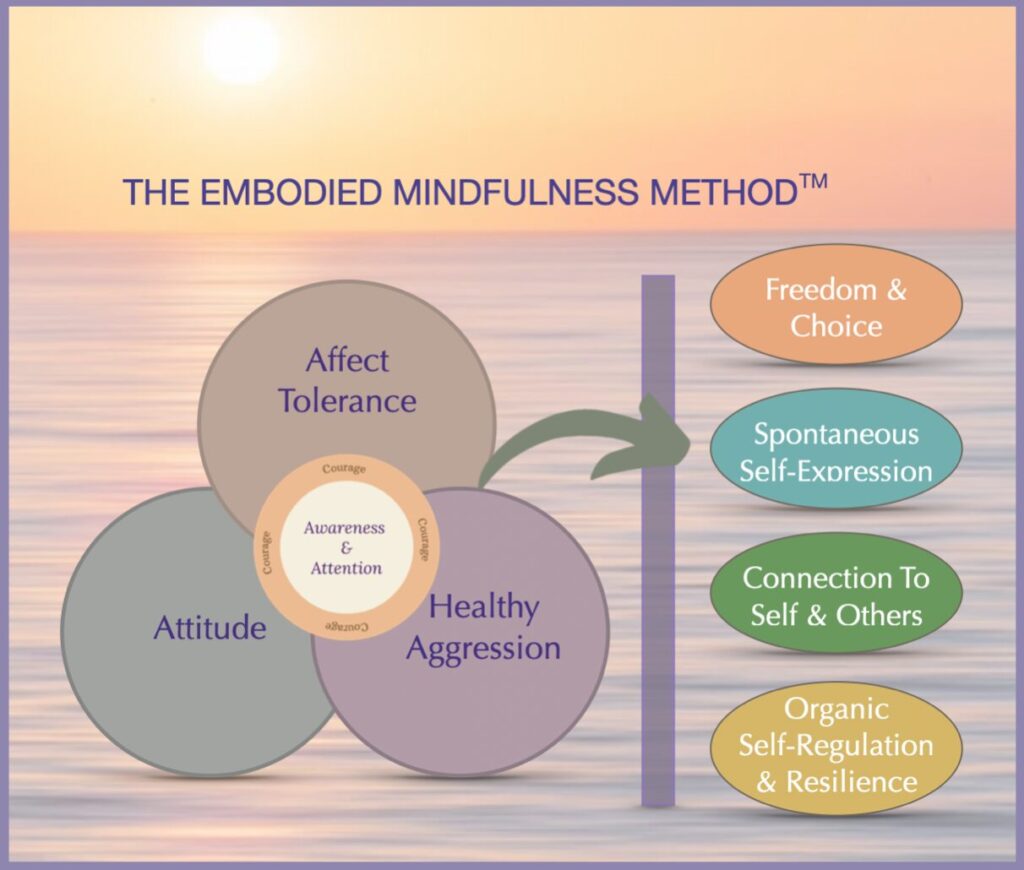

The Embodied Mindfulness Method™

The Embodied Mindfulness Method™ is the culmination of Dr. Parker’s experiential work over the last three decades. The method blends the wisdom and philosophy of the East (Aikido and Zen) with the science and psychology of the West (the Feldenkrais Method® and Somatic Experiencing®). Central to all four of these disciplines are the concepts of awareness, focused attention, potentiality, and the transformation of consciousness. EMM brings together the key insights from these various approaches into one modality.

The intention that underlies and permeates the Embodied Mindfulness Method™ is to lead individuals to a greater sense of freedom & choice, a greater sense of connection to themselves and to others, more spontaneous self-expression and organic self-regulation & resilience.

A transformational model blending ancient wisdom and modern science

Use the purple buttons below to explore the concepts in the EMM diagram.

Awareness of and Attention to: The Body-Mind System

I work with a broad spectrum of individuals.

- Some people come because they feel stuck in some way – unable to move forward in a particular area of their lives.

- Some people may come seeking insight into a particular behavior or a habitual emotional response (e.g., procrastination or a fear of intimacy).

- Some people may come seeking a greater sense of freedom and choice, more spontaneous self-expression, or a greater sense of connection with themselves and with others.

- Some people are seeking organic self-regulation and resilience (i.e., a more natural responsivity and adaptability to the stressors in their lives).

- Some people come with serious and debilitating stress-related conditions. Stress-related conditions often manifest in physical symptoms that have no organic cause. (Two of the most common are physical pain or a collection of symptoms that have been labeled/diagnosed as an “auto-immune” condition.)

Wherever you fall on that spectrum will determine which of the components listed below will be most important for you (in terms of increasing your awareness). For seriously ill people, with long-standing stress-related conditions, heightening awareness of many of the components of the body-mind system may be necessary. For others, heightening awareness of just two or three of the components will be enough to move you toward what you desire for yourself.

The Breath

- Awareness of the quality of the breath (deep/shallow; slow/rapid; flowing/staccato; effortless/forced; free/restricted)

- Awareness of how the breath changes from moment to moment in response to our environment (internal and external).

Gaining awareness of the breath helps you to become aware of internal states and internal state changes that you otherwise might not be aware of. For example, if you are feeling something that you are not aware that you are feeling (yes, that IS possible), your breath will change. By noticing the change in your breath, you might be alerted to the feeling that you were not present to. And, as Dr. Diana Fosha points out in her book, The Transforming Power of Affect: “Knowing the full extent of our feelings empowers us to take effective action on our own behalf.”

Gaining awareness of the breath helps to move energy. And as we know from the eastern health traditions, “stuck energy” is the cause of most psycho-emotional and physical disease (i.e., a lack of ease physically or psycho-emotionally).

Gaining awareness of one’s breath can also help with “oxygen debt”. Oxygen is extremely important for the function of our brains, nervous systems, and all internal organs. It also purifies the blood stream. “Oxygen debt” (i.e., oxygen deprivation) has been implicated in both chronic fatigue conditions and chronic pain.

Feelings

Feelings, as defined in the Embodied Mindfulness Method, consist of anything that can be felt in the body. This includes:

- Sensations: e.g., buzzy, burning, electric, fluid, heavy, paralyzed. quivering, shaky, spacious, loose, light, tense, tingly, trembly, bubbly, warm, twitchy, etc.

- Basic Emotions: Emotions, as defined in the Embodied Mindfulness Method, are feelings that are encoded in the facial muscles and thus expressed through the face. According to Paul Eckman (expert on human expression and the physiology of emotion), these “basic emotions” are not culturally determined, but rather, universal across human cultures and thus biological in origin. This means that sadness on the face of a Japanese person will likely be recognized as sadness by someone from another country. These “basic emotions,” according to Paul Eckman are: sad, angry, happy, fearful, disgusted and surprised.

- Other Feeling States: There are other “feeling states” experienced in the body but, unlike emotions, they are not encoded in the facial muscles. Examples of “other feelings states” might include: encouraged, hopeful, optimistic, appreciative, carefree, strong, uneasy, disappointed, bored, bewildered, downhearted, strong, powerful, rebellious, relieved, touched, etc.

The Felt Sense

The “Felt Sense” is a term coined by Eugene Gendlin. It refers to a bodily awareness of a situation, person, or event. This “bodily sense of things” encompasses everything you feel and know about the given subject at a given time. This “bodily sense” communicates this information to you all at once rather than detail by detail. In other words, the felt sense comprises everything that informs your internal experience.

Neuromuscular Tension Patterns (NTPs)

The less excessive tension we carry in our bodies, the healthier we will be. NTPs are a critical component in most of what ails us physically (including, but not limited to, chronic pain). NTPs can also be responsible for keeping us locked into a pattern of psycho-emotional distress.

- The earliest interaction of the child with the external world is entirely physical. To state this another way, our muscular and postural patterns were formed at a time when we were wholly dependent on another for our survival. The earliest emotional experiences become, therefore, associated or linked with muscular and postural patterns. As a result, our emotions are reinstated when there is sufficient resemblance between the present body state and the original one.

This would seem to be reason enough to dismantle our NTPs. NTPs keep us locked into infantile emotional patterns that no longer serve us as mature adults. In fact, these infantile emotional patterns invariably have ill-effects on our adult relationships and they often keep us locked in relationships that are familiar in some way, yet wholly unsatisfying.- It is difficult to feel open, lighthearted, joyful and carefree when our bodies are filled with NTPs that keep us locked into states of anxiety, depression, anger, etc.

- It is difficult to feel powerful and capable (rather than powerless and incapable) when our bodies are filled with NTPs that keep us locked into a collapsed posture of helplessness and/or shame.

- It is difficult to behave or express ourselves spontaneously (rather than compulsively) when our bodies are full of NTPs. NTPs, by their very nature, inhibit spontaneity.

- NTPs are a critical factor in the inner conflict that everyone suffers from (it is only a matter of degree). And inner conflict is, in my mind, one of the primary reasons we feel “stuck” in some way – unable to grow and move forward in our lives. For example: What is at the heart of the tendency to procrastinate? The likelihood of it being internal conflict is very high.

- NTPs are also one of the primary factors underlying most physical ailments (including chronic pain, but not limited to chronic pain). Whether you have strained a knee or shoulder, have some chronic pain issue in a certain part of the body, or experience visceral distress (organ-related symptoms), awareness of NTPs will be a fundamental aspect of your healing process. You might be able to heal “acute” injuries without such awareness, but it is quite likely that, if you don’t become aware of NTPs, you will likely injure yourself again and again, develop a worse condition that may require surgery, or have some other symptom of ill-health emerge.

Impulses

- Defensive (e.g., the impulse to fight, to flee, or to freeze). Sometimes these defensive responses get “stuck” in our body-mind system, and we will habitually resort to them when stressed (whether we need to or not). So it is important to become aware of them because these “stuck” impulses can be responsible for an imbalance in our autonomic nervous system. Imbalance in our autonomic nervous system can lead to a variety of stress-related conditions. (Experts are now estimating that 75% -90% of all doctor’s office visits are for stress-related ailments.) Furthermore, these “stuck defensive impulses” are quite often the source of chronic pain in a particular area of the body that has no organic cause.

- Expressive (e.g., the impulse to dance, to sing, to connect with another, to hug someone, to kiss someone, to comfort someone, etc.). Expressions of any kind, when stuck in our system, lead to excessive tension. That is what tension is: suspended action. Excessive tension, as I mentioned above, is a critical component in most of what ails us physically and also what keeps us locked into a pattern of psycho-emotional distress.

Habitual Physiological Responses to Stress

I am referring here to the physiological response. The fight and flight responses, for example, lead to certain neuromuscular tension patterns. These responses also set in motion certain physiological processes (e.g., pupils dilate, heartbeat accelerates, bronchi dilate, digestive processes are inhibited, there is a secretion of adrenaline, etc.).

When we become aware of these more subtle processes, we can use them as “early warning signs” that we are currently feeling stressed. You would think that we would know when we are feeling stressed; but that is not true. As Neuroscientist Dr. Antonio Damasio states in The Feeling of What Happens: “There is no evidence that we are conscious of all of our feelings, and much to suggest that we are not.” That includes feeling “stressed”. When we can become aware, early on, (by detecting these “early warning signs”) that we are feeling stressed, we can learn to settle our physiology before we feel overwhelmed and unable to cope.

Habitual Emotional & Behavioral Responses to Stress

- When stressed, for example, you may habitually become angry and “act out” in some way (pick a fight, become confrontational or attacking of another, etc.).

- When stressed, fear might be your default emotion, and you may “act out” in some way. Usually this leads to a variety of avoidance behaviors. You may, for example, isolate yourself and/or avoid the person or situation that is stressing you.

- When stressed, your default emotion may be fear and you might freeze and/or dissociate. You may stop feeling altogether. You may “numb out”. This kind of shutting down can, in turn, lead to undesirable states like depression or lifelessness. This kind of shutting off from our experience can also lead to many undesirable physical conditions, such as chronic pain and chronic fatigue (to name just a few).

Habitual Adaptive Strategies in Response to Stress

All of us develop adaptive styles (coping mechanisms) in the process of learning to survive in the physical world. These coping mechanisms most often develop around 5 central themes:

- Contact/Connection

- Need/Nurture

- Dependency/Trust

- Autonomy/Individuation

- Love/Sexuality

Usually one theme will emerge in our lives and in our behaviors in a prominent way. Others themes will emerge from time to time as well. But the prominent theme is usually the one that will wreak the most havoc in our lives. Most often these strategies have outworn their use. Nonetheless, we continue to use them (without awareness that we are doing so). These strategies, when we remain unaware of them, limit our freedom and choice, our spontaneous self-expression, our connection to ourselves, and our connection to others.

Perceptions

I am referring here to how we organize and understand sensory input. We can “perceive”, for example, that a person or situation is dangerous. Perceptions may, or may not, be fully accurate. And we may, or may not, be conscious of our perceptions. But we will act on them nonetheless. So it is important to become more conscious of our present moment perceptions.

States of Mind

States of mind are temporary, but last longer than a mood or an emotion. What Neuroscientist Dr. Antonio Damasio said about feelings in general can be applied also to states of mind: “There is no evidence that we are conscious of our present state of mind, and much to suggest that we are not.” Indeed. It is my observation that we can be equally unconscious of our feelings, emotions and our present state of mind.

Impermanence of Mind

It is a self-evident fact that there is nothing permanent about our thoughts, our perceptions, or our state of mind. For example, we can think a thought, obtain new information, and then discard that thought, and think another thought. We might be in a very uplifted state of mind in one moment, and then receive a distressing phone call or email, and suddenly find ourselves quite distressed. Nonetheless, many people behave “as if” their temporary state of mind is a permanent state of mind. Learning to be conscious, in the moment, of the impermanence of mind can be transformative in and of itself. And yet, in moments of distress, we seldom maintain awareness of this self-evident fact.

Conscious Thoughts

Again, it seems odd that we could have a thought, and not be aware of that we just had that thought. But, as it turns out, indeed we can! The classic example of this is self-judgment. Most people are wholly unaware of just how often they have thoughts of self-judgment throughout the day.

I was once working with a gentleman who was particularly prone to judging himself. When he would do it in session, I would, of course, draw his attention to the judgment. But I also suggested to him that he might want to track that throughout the week – how many times a day, he judges himself. He got the idea to get a little counter, which he kept in his pocket. Every time he would catch himself judging himself in some way, he would click the counter in his pocket. The next week, when he returned for his session, he told me that the first day, the counter was well over 100 at the end of the day! And yet, prior to that week, he had no idea that he had that many thoughts in the form of self-judgments (on a daily basis).

What if, throughout the day, every time you expressed something, someone was there to judge you? What if every time you made a decision, someone was there to judge you? What if every time you had an idea about something, someone was there to judge you? What if every time you had an emotional response to something, someone was there to judge you? What do you imagine you would feel like at the end of the day? Clearly it would behoove us to become more aware of such thoughts.

Implicit Phenomena

“Implicit phenomena” refer to any part of our present-moment experience that is cut off from our conscious awareness, but nonetheless serves to prompt our behaviors (usually our “unwanted behaviors”). Part of the EMM process is helping one to become aware of these implicit phenomena.

- Implicit meanings: Basically you make the behavior of another person “mean” something. The meaning that you make may or may not be accurate. But whether it is accurate or inaccurate, it is wholly unconscious. For example, on some unconscious level, you may believe that your friend behaved the way that they did because you are not worthy of their love or attention. In these cases, you do not have a conscious thought that you are unworthy of love and attention. But it is there, hovering, so to speak, somewhere in your consciousness. In these instances, there is a very good chance that this implicit meaning will contribute to your behavioral response.

- Implicit memories: You can have a memory from the past, but you have no way to know that it IS from the past because it is not encoded in the brain in the same way that explicit memory is encoded. Behaviorally though, you will still respond to the memory. You simply won’t understand WHY you responded as you did. Or you will likely attribute your response to the present moment situation – what another said or did, for example – and believe that they are the cause of your response. In fact, though, the cause of your response is the memory that you are not aware of.

- Implicit Beliefs: You believe something that you don’t even know you believe. You may, for example, deep down inside, believe that you are different than everyone else, and/or that you don’t belong. Or you may believe that you are fundamentally flawed, even though you never actually had either of those thoughts. Nonetheless, you behave “as if” you believed it. So, often times, we can deduce these implicit beliefs from observing our behaviors. You may notice for example that you behave “as if” you believed that you are fundamentally flawed. Or you behave “as if” you believed that you don’t belong. Again, implicit beliefs inform and often dictate our behaviors, even though we are unaware that we have the belief.

- Implicit Identities: You might “identify” with a role: “I am teacher.” “I am a Corporate Executive.” “I am a mother/father.” But these are identities that you are aware of. We also have “identities” that we are unaware of. “I am the person who ______________________.” You could fill in the blank with almost anything. But here are some examples:

- “I am the person who doesn’t have any needs.” “I am person who always takes care of everyone else.”

- “I am the person who everyone depends on. I do not depend on anyone else.”

- “I am the person who everyone comes to for help. I don’t need the help of others.”

- “I am the person who always gets taken advantage of.”

- “I am the person who is always strong; others are weak.”

- “I am the person who always gets rejected.”

- “I am the person no one wants around.”

- “I am the person who always gets blamed for everything.”

- “I am the person who doesn’t have any needs.” “I am person who always takes care of everyone else.”

Interpersonal Behavioral Patterns (IBPs)

We all have these IBP’s. It is a matter of how much these patterns impact our life and our relationships. For some, these patterns lie at the heart of why their relationships are not working. For others, these patterns keep them out of relationship all together . . . or certainly out of intimate relationship. The reason for this is simple. The greater the intimacy, the more likely these patterns will emerge.

You might choose, for some explicit reason, to not be in an intimate relationship. But if you chose to be in an intimate relationship, and you are not, chances are that one or more of these IBP’s is at play. Similarly, if you are choosing to stay in a relationship that is familiar, but unsatisfactory, quite likely one of these IBP’s is at play. If you are in an intimate relationship, and despite your conscious intentions, you continue to behave in habitual ways that do not serve the relationship, chances are that one or more of these IBP’s are at play. Whichever is the case for you, quite likely you are unaware of the particular relational pattern.

How did you learn to manage relationally? How did you learn to stay safe AND be in relationship? I am not speaking of what you were told to do — not what you were explicitly taught — not the “social mores” — not the “mind your P’s & Q’s” kind of learning. Rather I am speaking of the implicit learning — that which we learned that we don’t know we learned. This implicit learning happened very early on — at a time when we were wholly dependent on another human being for our survival. Without awareness, we, as adults, will continue to respond in the same manner. We will do so even though it is no longer necessary to do so. We will do so, even though these strategies no longer serve us — personally or relationally.

But as we become aware of these themes — these strategies and styles of relating, we can begin to transform them into more mature responses that serve both ourselves and our relationships. Ultimately, this leads to:

- More freedom and choice in relationships.

- More spontaneous self-expression in relationship.

- Greater organic self-regulation in relationship.

- Greater ability to co-regulate in relationship.

- Greater emotional resilience in relationships.

Over-Coupling & Under-Coupling Phenomena

Over-coupling is, in essence, a conditioned response. In over-coupling, parts of our experience are “stuck” together. For example, a Veteran of War hears a car backfire and he is immediately filled with terror and instinctually ducks for cover. In actuality, there is no real reason for the terror (a car backfiring is not life-threatening). And in actuality, there is no reason to duck (as there is nothing coming his way that could potentially harm him). Nonetheless, the Veteran habitually responds in this way, despite the fact that there is no need to do so. This is “over-coupling”.

We all have these kinds of “over-couplings”. Most often, we are not aware of them. Nonetheless, without awareness, and without dismantling the “over-coupled sequence”, much like the Veteran, we will continue to respond/behave in the habitual manner (even though it no longer serves us or those with whom we are in relationship).

Under-coupling is the opposite; there are missing pieces. We may, for example, be experiencing an emotion (but that emotion is cut off from our conscious awareness). A person may behave as if they are angry, but if you ask them if they are angry, they will say, “No.” They are not being dishonest; they honestly do not feel the anger. Again the statement from Neuroscientist Antonio Damasio is apropos here: “There is no evidence that we are conscious of all of our feelings, and much to suggest that we are not.” We can, however, in EMM sessions, become aware of these “split off” aspects of our present moment experience.

Natural Processes Within

I am referring to processes like: Ebb & Flow; Expansion & Contraction; Movement, Flow, Change & Transformation; The Dynamic Interplay of Polar Opposites.

- Attitude

- Affect Tolerance

- Healthy Aggression

The word “attitude” as it is used in the Embodied Mindfulness Method refers to:

How you respond to your experiences? For example:

- Do you respond with a sense of dread or with a sense of excited anticipation?

- Do you respond with a lack of interest or with a sense of curiosity?

- Do you respond with acceptance or denial?

How you judge your experiences? For example:

- As “good” or “bad”?

- “Positively” or “negatively”?

- As “useful” or “not useful”?

- As “pleasant” or “unpleasant”?

What you have learned to pay attention to or, conversely, what you have learned not to pay attention to? For example:

- If you are in pain, is your attention focused on the part of you that is in pain, or the part of you that is not in pain?

- If your life is not quite working out the way you had hoped, is your attention focused on the part of your life that isn’t working, or the part that is?

- Is your attention drawn to what another does that pleases you or to what another does that displeases you?

- If you are having challenges reaching your desired goals, are you focused on what you can do, or what you have not been able to do yet – on what you have achieved, or what you have not achieved?

How you relate to yourself? For example:

- Do you respond to yourself with judgment or with compassion?

- Do you respond to yourself with a lack of interest or with a sense of curiosity?

- Do you respond to yourself with acceptance or with denial?

- Do you respond to yourself by embracing the various parts of yourself? Or do you respond by rejecting the various parts of yourself?

Part of the EMM process is helping you to become aware of these (often-times habitual) ways of responding. When we become aware, it frees us up to chose otherwise.

“Affect tolerance,” as it is used in the Embodied Mindfulness Method, is the capacity, in any given moment, for tolerating your internal state (i.e., your feelings, sensations, and emotions). Having little capacity to tolerate one’s internal state lies at the heart of most if not all dissociative conditions, chronic pain conditions (that have no organic cause), many addictions, and many anxiety and depressive conditions. Quite likely it is also a factor in some pseudo seizure disorders. Indeed, the capacity for affect tolerance is often the “missing piece” for those who work with, or suffer from, these conditions.

In EMM Sessions, you are constantly building your capacity for tolerating more intense internal states (both those perceived as “positive” and those perceived as “negative”). As poet and philosopher Kahlil Gibran wrote: “The deeper that sorrow carves into your being, the more joy you can contain.”

In EMM Sessions, this capacity is increased a little at a time, in order to not overwhelm the capacity of the person “in the moment”. When you increase your “affect tolerance”, you enhance your ability to self-regulate (so that you don’t have to self-medicate). You also increase your sense of freedom, you give yourself the gift of choice, and you experience a greater connection to yourself and to others.

Part of what we do in EMM sessions is restore access to one’s natural aggressive instincts and help individuals to integrate and utilize healthy aggression. By healthy aggression, I am referring to the life force within us all — the self-expressive drive to create. In the Japanese Martial Art Tradition, this aggression is thought of as a “forward moving” energy — that which vitalizes us — that which gives us strength and courage.

Healthy aggression is a motivational force. It is a transformational energy. It is a force that leads to assertive and bold behavior. It is the energy responsible for our determination. It is the energy that leads us to take effective action — the energy that moves us energetically forward in pursuit of our goals. This healthy aggression is, in short, our vitality and our aliveness.

We need access to this energy in order to be able to set boundaries with others when needed. Without access to this energy, we do not feel safe. It would be tantamount to walking through life naked, with our hands and feet tied together. Anyone could do anything to us at all. And there would be nothing we could do about it.

When we have shut down this healthy aggression — when we do not have access to this aggression, or when we deny it — we become fearful, depressed, passive, lifeless, powerless, uninspired and uncreative. We succumb to a state of hopeless resignation. When we lose sight of this healthy aggression, we lose sight of our own power — our ability to impact the environment.

When we lose sight of this healthy aggressive instinct, we lose our fighting spirit. We find ourselves devoid of the energy and motivation to fight — not other people, but rather, the true enemies of mankind — e.g., ignorance and injustice. Last, and perhaps most importantly, when we lose sight of this healthy aggression, we diminish our capacity for creative self-expression.

Ready to Learn More?

Explore the benefits of EMM, testimonials, and more throughout this section of our website.